Rural Science An Applied View of Science

(Remember these notes are from around 1984)

INTRODUCTION

Rural science is the science and technology of plant and animal husbandry, both for primary food production and as an asset to the aesthetic qualities of life.

In essence it is an appreciation of the factors which affect the long term

well being of the land and plants and animals. This develops an

understanding of man’s utilisation of the Earth’s resources and the science

and technology he applies to the production of his food, and to the quality

of his environment for both his amenity and leisure activities.

Historical development

Although there are records of agricultural education taking place in schools

from as long ago as 300 years, the terms ‘rural science

‘

and ‘rural studies’ only appeared in the second decade of this century.

Activities involving plant and animal husbandry increased rapidly in

secondary schools during and after the second world war as a consequence of

the ‘Dig for Victory’ campaign. Following the formation of several county

associations of teachers involved in the subject, a National Rural Studies

Association was formed in 1959. Ten years later the Schools Council Working

Paper No. 24, ‘Rural Studies in Schools’ was published, this being followed

by the Schools Council sponsored ‘Project Environment’.

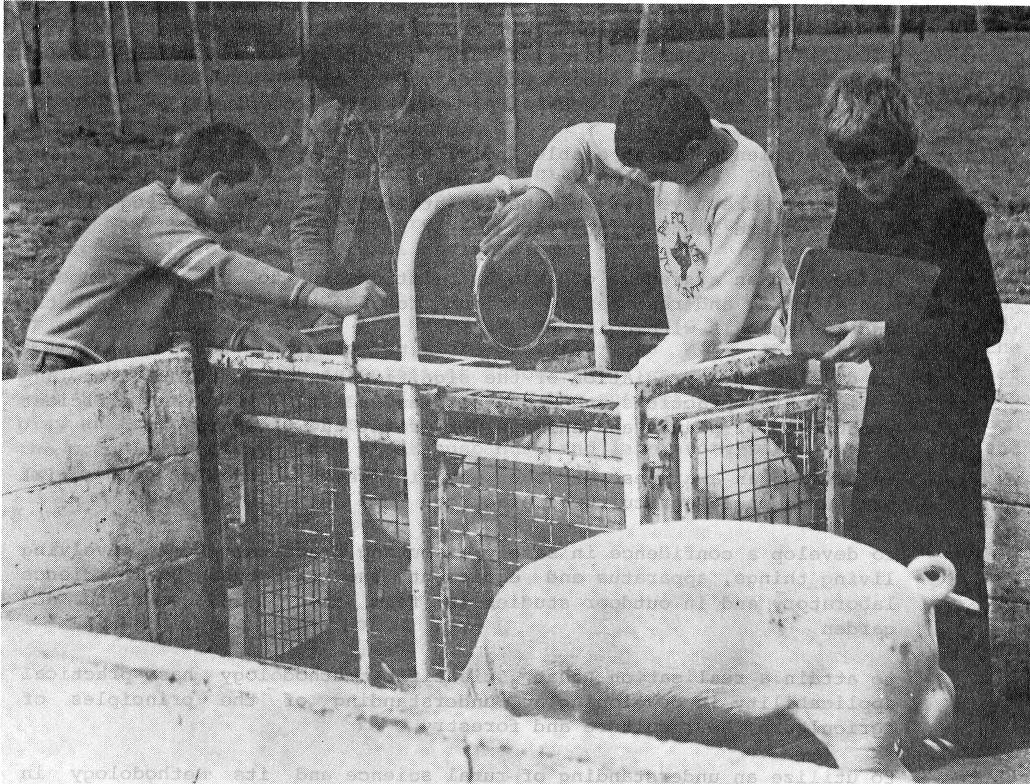

growing plants and experimenting with them under controlled conditions

in a greenhouse or a garden planned for scientific studies

studies of farms and natural habitats

maintaining a plot in a state forest

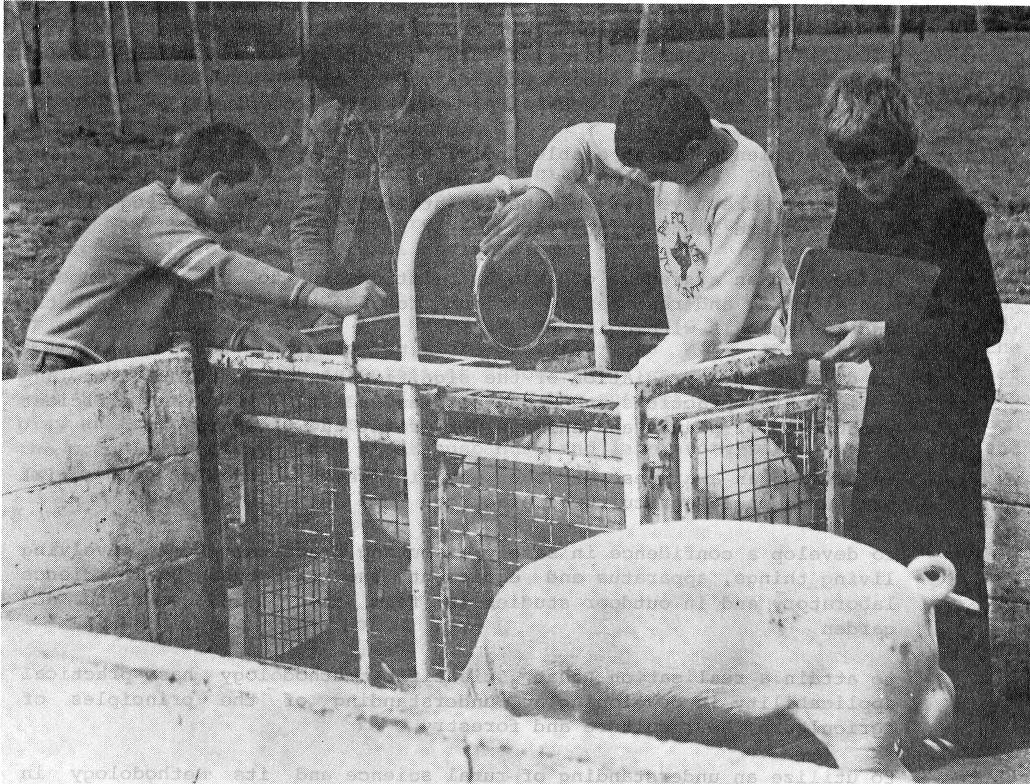

running a school livestock unit, sometimes even a small school farm

laboratory investigations linking work with plants and animals to

scientific principles.

At schools which still retain this approach, the content of rural science is characterised by the study of aspects of agriculture and horticulture. Thus it is concerned with the production of plants and animals which have food or amenity value. The educational value of firsthand experience and investigation has long been appreciated, together with that of children being involved in the long term care of plants and animals.

Rural science is a stimulating and vital area of applied science, in which rapid

progress is being made. Unfortunately this is not always reflected in school

curricula and particularly in some examination syllabuses more specifically the

husbandry and investigative aspects of the subject have sadly decreased.

It is clear through such developments as city farms that the urban population is

no longer prepared to remain unaware of the rural systems

—

and why should they? Now, more than ever before, there is a real need to educate

so that the public can appreciate the rural environment.

It is suggested that in order to be of most value to the widest ability range of

children, the scope of rural science should not be too broad. Investigations of

town planning, for example, are more appropriate for the geographer than for the

scientist at school level, and the past inclusion of such topics has blurred the

definition of the subject area. Rural science can play an important role in

scientific, aesthetic and moral education, through the practice of animal and

plant husbandry and laboratory-based activities and investigation of local

habitats.

THE AIMS OF RURAL SCIENCE EDUCATION

Rural science is taught as a part of the science education within school

curricula and therefore the aims of science education, as stated by the

Association for Science Education in ‘Education through Science’, are naturally

embodied in part in the aims of rural science. Rural science as a distinct part

of the curriculum should provide young people with a structured experience which

will satisfy the general aims as stated below.

The aims of rural science are to enable individual pupils:

These aims provide the framework within which any rural science teacher can

arrange a personal scheme of work to achieve particular objectives for school

pupils at different phases of their education. The aims also indicate that rural

science has an intrinsic value within the total science curriculum offered to

pupils in compulsory education.

THE IMPORTANCE OF RURAL SCIENCE IN THE SCHOOL CURRICULUM

Rural science has, in its own right, much intrinsic scientific interest, but

there is a danger of moulding rural science to fit into the pattern of

traditional science courses. Scientific concepts in rural science arise from the

basic investigatory nature of the subject and a holistic approach. Scientific

principles are applied to the solving of immediately perceived and identifiable

problems arising from the pupils’ own observations of a practical situation

which is generally initiated by their experience with the plants, animals or

land for which they are responsible. Pupils are able to study plant and animal

physiology and biochemistry by observation and experimentation on the whole

organism, on a different scale to that usually possible in the laboratory, with

a view to maximising its health, well-being and profitability, instead of an

academic approach from a cellular or even a molecular level. At the same time,

of course, a thriving rural science department can and should support with

materials and ideas the teaching of the other sciences.

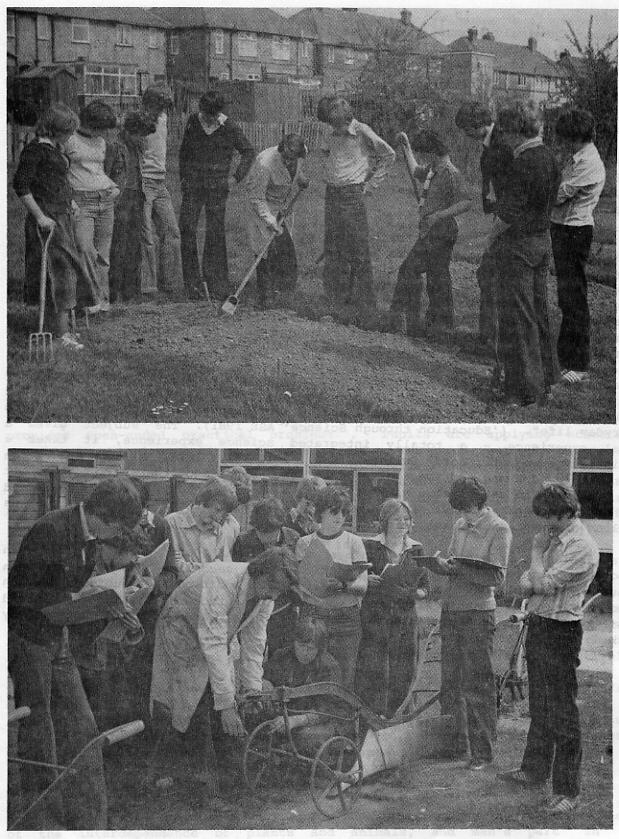

Clearly rural science students learn many practical skills when handling,

observing and investigating plants and animals. Some of these are of a general

scientific nature, others are more specific to agricultural science. Likewise

pupils learn cognitive skills such as analysis and interpretation of data,

hypothesis formation and testing, and the planning of investigations

-all

of which are clearly high order scientific skills. Pupils are given the

opportunity for original scientific research as individuals, or within a group

project with the important communications and interactions in the group.

The study of rural science involves the pupil in a much more personal view of

the scientific world than do the traditional sciences. This personalised view

can be at the exciting, emotional level of seeing a birth (or a death). The

pupil is placed in his social and historical context as fundamentally a producer

of food. Pupils perceive value judgements when analysing modern farming

practices and the welfare of animals or the conservation of the natural

environment. Rural science provides opportunities for the learning of skills for

the pursuit of a lifetime of leisure interests or the gleaning of information

leading to original research. It is the area of science which most readily moves

into a direct and rewarding concern not only for the pupil’s own plants and

animals but also for his whole environment and for the general global problems

facing modern Man.

The need to care

for living materials either

in the school or through observations on local farms has often resulted in a

greater motivation and interest than in the traditional more detached academic

disciplines. It has also been a considerable help to many pupils in their future

working lives and increasingly in their leisure time since so much of the

subject has been self-evidently meaningful and helpful and has been one of the

few areas of the school curriculum in which pupils could show a creative and

caring concern for those in their charge. It has given an increased sense of

responsibility in both the social and scientific senses, and produced a

long—term framework in which the pupil could operate.

A well established feature of this method of working is the way in which new

insights and points of contact are gained by the teacher as children demonstrate

a knowledge and expertise usually totally hidden in more academic pursuits.

Behaviour, too, can often change as the pupils exercise a new responsibility and

thereby improve their own self—image and gain a new sense of purpose and

respect, as they care with a jealous affection for their plots or stock. In

short rural science can lead to many interesting “happenings”, which can enrich

both the teacher and the pupil and improve relationships between them. In the

future, the use of microcomputers and monitoring systems will enable new

investigations to be undertaken in the laboratory and in the field, and open up

new possibilities for children to continue to carry out experimental work

—

“experimentation” in its true sense of exploring unknown situations, rather than

carrying out merely routine exercises and simulations which so often pass for

experimental work in schools science.

The time scales in the practices of horticulture and agriculture are often very

different from those experienced in traditional science. They provide

opportunities for students to study in a more relaxed and open ended way. There

is not the same pressure to complete and ‘parcel up’ a piece of study. Many

pupils respond to the slower rates of progress of plants and animals, and do

benefit from the less frantic disciplines imposed. The realisation of the

inevitability of seasonal progress and change is more important to urban

children than ever before.

Thus rural science is an excellent vehicle for teaching the processes of

science. Since this is a controversial and highly disputed area of the

educational debate, we have taken as our working model that used by the ASE in

‘Education through Science’. Rural science provides children with a basic

knowledge and understanding of the world in which they live and moreover by

looking after living things they develop a responsibility for the plants and

animals in their care. The subject also develops an enquiring mind and provides

open-ended practical problems

.

Pupils are applying scientific concepts to a real situation. It is apparent to

the pupil that these concepts are both relevant and necessary. The managerial,

the practical and the manipulative skills needed to manage livestock and crops

can be developed from a simple level up to a sophisticated understanding as the

pupil matures. Through the study of rural science the pupils can extend their

scientific knowledge and interest, and are helped to communicate with interested

bodies in industry and commerce at local and national levels.

Agricultural decisions often involve the choice between the lesser of two evils,

weighing the advantages against disadvantages, when considering the financial

and social implications of one’s actions. The use of fertilisers, pesticides,

intensive agriculture such as battery farming is neither wholly right nor wholly

wrong, they can be used wisely or irresponsibly. Pupils, through rural science,

have the opportunity to look at such issues objectively.

The horticultural and agricultural industries are, of course, at the forefront

of the application of new techniques in macro— and micro—technologies, and the

child’s direct experience of these technologies in local industries ensures that

a study of rural science can encompass the oldest traditions of stock rearing

and cultivation, as well as the most recent developments at the forefront of

Man’s knowledge and manipulative skills when producing food and controlling the

environment in which he lives.

Rural science also provides a vehicle for presenting to the pupil the concept of

the interdependence of plants and animals, and man’s part in the ecosystem.

Since the populated world revolves around an agricultural foundation, it can

sensibly be demonstrated that good husbandry and planning are essential criteria

if shortage and suffering are to be avoided. The agricultural industry in this

country is now highly sophisticated with the widespread use of computers for

recording, planning and projection of targets. Chemical weapons, plant breeding

and biological pest control can all

be broached or profitably illustrated in rural science. The world scale of these

problems is clearly a vital issue of which young people should be aware. If the

problems are to be overcome scientists will play a key role. Thus agricultural

science can be seen to interact with other agencies in international society,

and pupils may learn how a scientific perspective can complement other

perspectives or ways of organising knowledge and inquiry. Science makes a

contribution not only to our cultural heritage but to the whole world economy.

The conflict between science and society can be illustrated clearly in the rural

economy and pupils gain first hand experience of scientific inter-action.

The authors of ‘Alternatives for Science Education’ (ASE 1979) said: “a good

science education should seek to develop a range of intellectual skills and

cognitive patterns which help youngsters to handle the problems of growing up

in, and integrating with, a society that is heavily dependent on scientific and

technological knowledge and its utilization”. Rural science aims to develop in

pupils a sense of responsibility, self confidence, social awareness and maturity

in the practical approach to learning about living material.

Rural science is able to “stimulate, maintain and develop interest, to foster

curiosity, and to encourage a growing awareness of the diversity and

open—endedness of scientific inquiry and an appreciation of its relevance to

everyday life”. (‘Education through Science’ ASE 1981). The subject gives a

total experience

—

a totally integrated science experience, it takes a holistic view-point. Lord

Bullock (SSR, 201, 57, 1976) talked about the ‘monolithic, dehumanised image of

science’ and expressed the belief that it was possible “to establish a view of

it as a humane study, deeply concerned with both man and society; providing

scope for imagination and comparison as well as observation and analysis”.

Rural science endeavours to achieve these ideals and therefore has an important

part to play in science education in secondary schools, and can provide a

valuable base in earlier schooling. In addition the subject has an important

part to play in sixth form courses for students wishing to extend their

knowledge of science in a technological world, and who are not solely seeking a

traditional academic course.

Andrew Cadman (Chairman) -

Derbyshire.

Christopher Bateman - Yorkshire.

David Braithwaite - Yorkshire.

Eric Cowen - Devon.

Alyn Dalby - Cornwall.

Andrew Hart - Herefordshire.

Murray Mylechreest - Worcester.

Geoff Oliver - Cumbria.

David Robinson - Northampton

David Taylor - Staffordshire.

David Williams - Essex.

THE VALUE OF RURAL SCIENCE WITHIN

THE SECONDARY SCHOOL SCIENCE CURRICULUM

(From 1987)

1.

The contribution made by rural science to the curriculum is both

supplementary and complementary to that made by the other sciences. The rural

science contribution provides pupils with an understanding of man’s basic

technology

- agriculture —

and of how both scientific method and scientific knowledge

are used to develop methods of production in an economic and efficient manner.

Studies of the environment of agriculture show pupils how people make judgments

about uses of land, balanced with other factors such as maintaining an

ecological equilibrium, ensuring conservation of natural resources and living

things, and allowing for social factors.

2.

Rural science requires pupils to care for and maintain plants and animals

in a sustained manner over periods of time whilst also acquiring husbandry

skills. Rural science therefore has value in developing responsibility in pupils

and providing for their emotional development.

3.

The need for continual care for living things is allied, in some

instances, with long term experiments. In these circumstances pupils learn that

patience is a necessity in order to obtain experimental results.

4.

Rural science offers opportunities for pupils not only to learn about a

technology, but also to learn something about the creative design process of

technology. Pupils engaged in investigative work learn to apply science to the

solution of practical problems.

5.

In many instances, rural science concerns topics that do not require

conceptualisation in the same way as the other sciences, and thus

it is

suitable

for pupils of all abilities. Equally, rural science provides

an

intellectual challenge which requires abstract thinking and so is

demanding for the most able pupils.

6.

The practical work associated with rural science provides a particular

stimulus for many pupils because it requires study and the

use of skills associated with large scale situations which are perceived as

relevant to everyday life.

7.

For some pupils, rural science provides a stimulus for a leisure

activity, and for others

it

lays the foundation for a vocation. In

both cases, the interest will be based upon an experimental

approach to learning about agricultural topics.

8.

Testimonies to the value of rural science in the science education of

pupils have been reiterated at intervals and are found in publications such as

Schools and the Countryside

(1958, HMSO),

The Teaching of Rural Studies

(Carson, S. McB. and Colton, R . W., 1962, Arnold),

Rural Studies in Secondary Schools,

(Schools Council, 1969, Evans/Methuen) and

Rural

Science —

an Applied View

of

Science,

(1984, ASE).

These views were summarised by John Heaney in 1982:

Rural science has much intrinsic scientific interest and there is no need to

justify its existence by

reference to

traditional aspects of school

science

which have

too

often caused students to

reject Science.

The aims of science education have been considered in relation to Rural Science

and thus, for reference, the aims given by ASE in Education through Science

are stated below.